-

Methods of Contextualizing: Written Work

PART ONE In my personal practice, I tend to gravitate towards work that explores the minutiae of felt experiences. This often means that my research, referential materials and enquiries are less concerned with statistical information, leaning heavily qualitative over quantitative. Methods of Contextualizing asked that I disrupt this approach by tethering my iterations to a…

-

Methods of Contextualizing

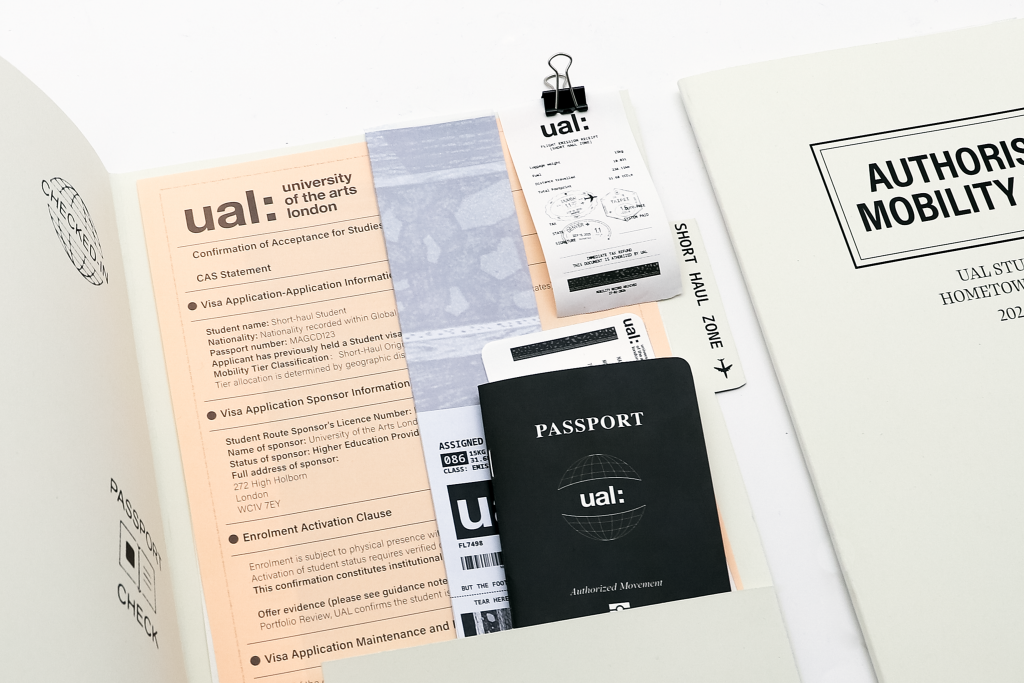

INITIAL EXPLORATION As a group, we decided to use student air travel as our primary data source. In the initial stages of this brief, we felt it would be best to experiment with our own, independent approaches, unifying the through-lines as the project progressed. While exploring the direction for my approach, I wanted to consider…

-

Methods of Translating

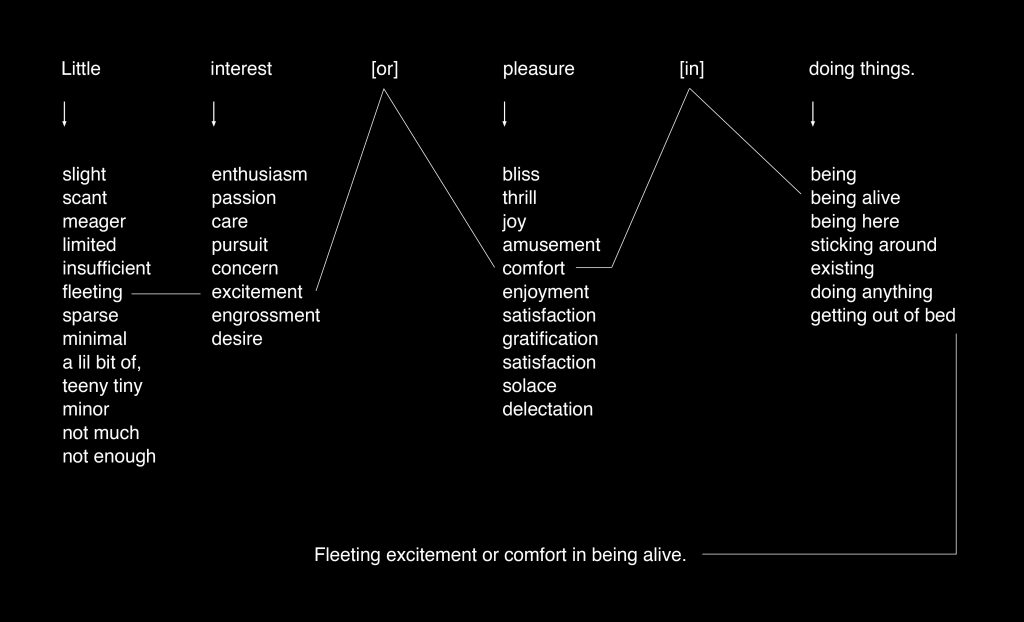

Three days prior to the deadline, I chose to change the direction of my work for this brief, selecting an entirely new source material. I received an email from my therapist, requesting that I complete an anxiety and depression assessment, clinically known as the PHQ-9 & GAD-7. This form aims to assess the severity of…

-

Methods of Translating: Written Task

Susan Sontag’s writing is so decisive that it often reads like a manifesto, hence why the Conditional Design Manifesto felt like an apt method for exploration. I wanted to approach the written task for this brief from a more critical perspective, rather than a direct translation of its meaning. It was important to consider style…

-

Methods of Cataloguing: Written Task

REFERENCES Crouwel, W. and Van Toorn, J. (2015) ‘The Debate’, in Poynor, R. (ed.) The Debate: The Legendary Contest of Two Giants of Graphic Design. New York: The Monacelli Press, pp. 21–38.

-

Methods Of Investigating: Written Task

While digesting this brief, I struggled to understand what I was looking for. I varied my search for a suitable site, ranging from Picadilly Circus to the quiet garden down the road. I couldn’t seem to define a viable method worth developing. In the first several pages of Georges Perec’s, Speicies of Spaces, I thought…

Got any book recommendations?